Charting Kala PAni

Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Indian Union Territory

This project was done in collaboration with Anamika Singh and funded by the Menschel Fellowship at Cooper Union and exhibited in February 2017 alongside the work of other Menschel Fellows.

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are group of islands at the confluence of the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea. Since 1000 the islands have experienced colonisation on the part of several empires. Though now part of India, indigenous tribes that predate colonial conflicts and presence are still the sole inhabitants of many of the islands.

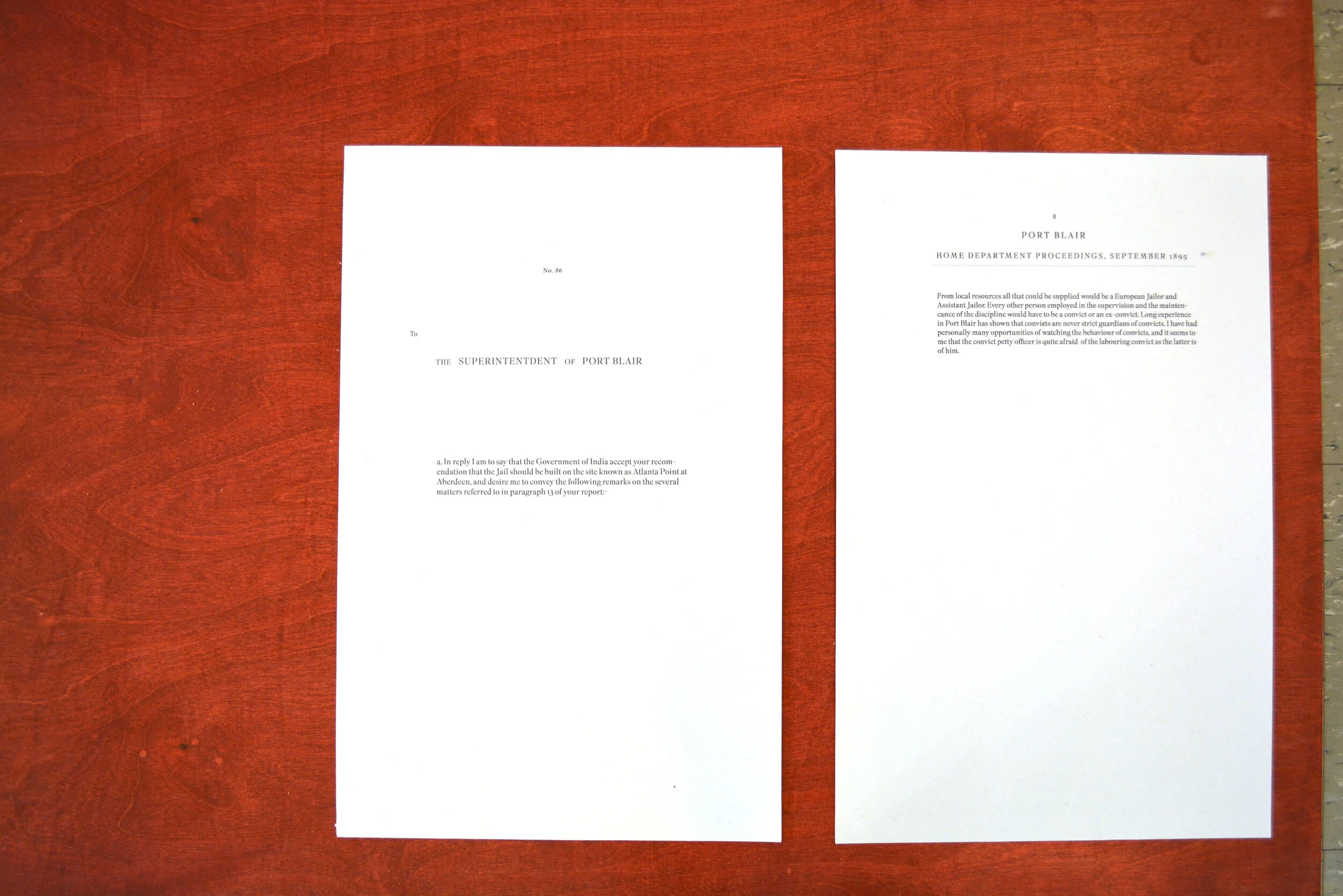

In 1858 the British erected a penal colony for political prisoners at Port Blair and in 1896 they built the infamous Cellular Jail, also known as Kālā Pānī. In Cellular Jail, the inmates were held in solitary confinement and controlled with a calculated combination of surveillance and physical violence. Beyond the walls of the prison resided British families, their children and their meals tended to by convicts.

Two decades after Indian Independence in 1969, the prison was converted into a national memorial and museum. In 2016 collaborating artist Anamika Singh and I traveled to the Cellular Jail to explore its history— a history that is twisted, but not alone. From the Ports of Gambia to the Bay of Guantanamo, colonial surveillance and exile have been embedded in infrastructure to inflict visceral violence. The field visit resulted in a body of work exploring relationships of gaze and violence and the entangled histories which now haunt these narratives.

Though the prison is geographically tucked away on one corner of one of the islands, the tower’s shadow looms over every one of the innumerable resorts and beaches. At the museum, nooses hang from the gallows, and mannequins resurrect the tortures of former inhabitants, inadvertently conflating the viewer with the torturer by replicating the original conditions of gaze. In evenings, the jail is re inhabited by its inmates through a son et lumiere, a nationalistic narrative portrayal of the memorial’s historical mythology.

The British lived on Ross Island, only a couple thousand feet away from the prison itself, enabling the prison to communicate directly with the British using a system of nonverbal signals that included using lights, gun shots, and semaphore. On the trip our research and work centered around the gaze that is built within the logic of the architecture of the prison itself, the gaze relationship between Ross Island and the prison, and the gaze of the contemporary conditions of the prison now, as a museum. These were all concepts that we brought out within the work itself as well as within our method of organizing the space.

On Ross Island, we wandered the ruins of the British governor’s residence. After Ross was hit by the tsunami in 2004, blocking Port Blair from the worst of the damage, hardly anything remains but his Italian floor tiling. Among overgrown foliage, stairwells lead to nowhere, their buildings having been swept up from beneath them. Tourists are free to wander the island for a small fee. At the prison, visitors can wander every cell in two of the three wings, to climb the up the buildings tower and onto the roof. From the tower, you can watch the goings on in and between the wings, or turn out to face Ross Island and the ocean.

Convicts who were due to be executed were placed in cells from which they could see the gallows and last ritual site. In the days before their death, they had to confront the place of their death. When someone was executed, lights would flash three times so that all of the inmates would know.

![[anamikasingh.me][16]Book_inside14.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922438803-LJBC2N562MYPVCWHTS1Z/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B16%5DBook_inside14.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][32]Book_inside17.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922438560-G8T3X614TY22PPDWLZET/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B32%5DBook_inside17.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][34]ScreenShot2017-05-28at10.38.06pm.png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922441494-Y8O33W0BIW67G39USSEY/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B34%5DScreenShot2017-05-28at10.38.06pm.png)

![[anamikasingh.me][55]Book_inside19.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922438318-JD6SZBYWPATGLSZ2ATYF/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B55%5DBook_inside19.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][67]Book_inside21.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922438299-POXPDE8PRX0MKPER2PBV/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B67%5DBook_inside21.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][136]Book_inside18.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922438946-WHWIH04HHKAXDBES6BD2/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B136%5DBook_inside18.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][170]Book_inside24.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922439798-TO2230F6FJYJA30VEU47/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B170%5DBook_inside24.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][216]Book_inside11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922439845-U65SA1TI479B7IHZ9KSF/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B216%5DBook_inside11.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][257]Book_inside21.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922440441-GCS8EIIGRMG0WIRC30PQ/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B257%5DBook_inside21.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][260]Anamika_Singh_KalaPani5.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922443596-7L3V539407J3F01FG61O/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B260%5DAnamika_Singh_KalaPani5.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][264]Anamika_Singh_KalaPani2.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922444234-Y987Z3HKF7QDEMNKIEGK/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B264%5DAnamika_Singh_KalaPani2.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][286]Book_inside11.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922444744-2JA4BY2LP8FCJDZLIKN3/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B286%5DBook_inside11.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][287]Book_inside15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922444539-8QI8NTYDT5DSVMGBT21J/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B287%5DBook_inside15.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][314]Book_inside4.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922444988-41S4BE0VD5TPUMV45V6O/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B314%5DBook_inside4.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][326]Book_inside22.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922445646-YWDGSMB28JU13R3XPW7P/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B326%5DBook_inside22.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][389]Book_inside10.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922446271-8CFGR1II904E2SNGB96L/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B389%5DBook_inside10.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][361]Book_inside17.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922451418-CN74I6Z3PES47RM5DHYX/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B361%5DBook_inside17.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][461]Anamika_Singh_KalaPani1.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922455218-5UXBOYI0GUDE762CNHBI/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B461%5DAnamika_Singh_KalaPani1.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][622]Book_inside25.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922451465-MI2K9EQHW9243SRK6PM9/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B622%5DBook_inside25.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][646]Book_inside7.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922454477-9TFI7PGQBIZA5YBWS3XI/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B646%5DBook_inside7.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][687]Book_inside15.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922452943-PK2CN0K6Z78EJWLPNN72/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B687%5DBook_inside15.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][747]Book_inside23.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922454912-J9P7T30XH7992V3APKQX/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B747%5DBook_inside23.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][756]Book_inside12.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922454541-U5DAVXD04HEAMTU56XUX/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B756%5DBook_inside12.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][875]Book_inside20.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922456021-0YC9SSV4WTZGATOFQ2V0/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B875%5DBook_inside20.jpg)

![[anamikasingh.me][989]Book_inside18.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f0659ef1e76ad0a2f2ff700/1600922456018-4ZMFITYNVZJ1CCKH0MKM/%5Banamikasingh.me%5D%5B989%5DBook_inside18.jpg)